For the majority of my time at University, I was with Edinburgh University Formula Student (EUFS), which is a student project competing in the prestigious Formula Student competition. I have established the autonomous racecar student project within the team, aiming to compete in the brand new competition class - Formula Student Driverless. Through the last three years, I have led a passionate team of about 60 students to 2 victories in the UK competition and have raised a budget of over £70,000. This allowed me to obtain practical hands-on experience in the topics I am interested in as well as develop my team working, management, leadership and communication skills. Most of all, however, this has experienced has shaped me as a person and allowed me to discover my passion for Robotics and AI.

The challenge

The main challenge of Formula Student is to develop the software for an autonomous racing car that can drive 10 laps as fast as possible around any unknown race track. The track itself is signaled by color-coded cones on both sides of the track.

Technical overview

Throughout the 3 years in the team, I went from no robotics experience to designing a fully autonomous vehicle software stack which I think is surprisingly well built for a student project and I would even say is better than what I have seen used in some big companies.

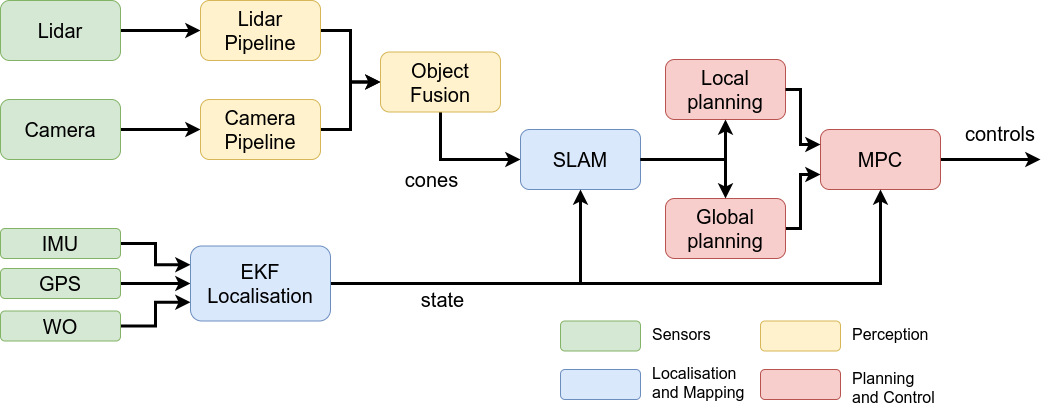

The stack itself, revolves around the classical see-think-act mobile robot cycle:

The car has two modes:

- Learning - This occurs during the first lap of the track in which the car builds a map and learns the dynamics of the vehicle. During this stage, a conservative path planning and control method is used as the car has a limited view of its surroundings.

- Racing - After the full map has been created, the car now has a superhuman view of the full track and is able to localize more precisely. In this mode, the vehicle uses a more aggressive path planning and control method.

Sensors

We equipped our car with a ZED Stereo camera and a Velodyne VLP16 lidar for perception. This configuration was chosen due to the complementary characteristics of the sensors. The camera is cheap, fast and can detect color but is relatively inaccurate at estimating the 3D position of objects. Whereas the lidar is excellent at finding the 3D position but is slow and can’t detect color.

For localization (state estimation), the car has wheel speed sensors at both rear wheels, a steering angle sensor, an IMU, and a GPS. All of these sensors complement each other and allow for some redundancy

Perception

The perception pipeline consists of an independent camera and lidar pipelines which run at the rate of their respective sensors and their detections are then fused with a Kalman Filter.

The camera pipeline uses the YOLOv3 neural network custom trained by us to detect cones in images which are then projected to 3D using the sparse stereo depth information from the ZED camera.

The Lidar pipeline is a multi-stage process where we first accumulate scans, apply motion correction, identify the ground plane and remove it, do some cluster filtering and then find objects using a grid-search algorithm.

Localisation

The vehicle state consists of kinematic and dynamic states.

The dynamic states are estimated using the localization sensors the car is equipped with, allowing us to determine the velocities and accelerations. This is done using an Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) to fuse the data from the Wheel Odometry (WO), IMU, and GPS.

For the kinematic states (position and orientation), we use the FastSLAM2 algorithm, which feeds of instantaneous cone locations from the perception pipeline and a prior position estimate from the EKF. A continuous map is then built while the car is in Learning mode, and when it finishes the first lap, the SLAM loop-closes, correct any inaccuracies in the map and then only localizes in racing mode.

Planning & Control

During learning mode (1st lap) we use a conservative planner which computes a path along the middle of the track and we use a look-ahead controller which calculates the desired speed based on the path curvature.

For the subsequent laps, we optimize the racing path with the minimum curvature using an elastic beam optimization algorithm and then we use a predictive model controller (MPC) to calculate the optimal trajectory.

Infrastructure

The full-stack, as described thus far, is based on ROS, and most of the code has been developed in C++ for optimal efficiency. We use GitLab for our development and utilize its integrated CI to manage our builds, dependency, do unit tests, and also do full integration tests when the whole stack is compiled together.

Simulation

A crucial aspect of our development is our open-source simulation called EUFS Sim We designed it in Gazebo to aid the development of all of our software except perception, as that is very difficult and time-consuming. Instead, our simulation models our perception pipeline from real-world data simulates our localization sensors, and uses a dynamic bicycle model to simulate the dynamics of the car. The result is a relatively light-weight a headless simulation that has aided our development fundamentally.

Bringing all of it together

This is the resulting architecture diagram:

Sadly, we never got to apply this as presented here to the real car due to bad timing with the COVID-19 pandemic. However, here is the data visualization of the whole stack in action in our simulation.

My experience

My personal development from this project has been so enormous that it is hard to describe it with words. It has taught me how to work in a team, communicate ideas; it has allowed me to obtain practical experience, hone my technical skills, and apply the theory I have learned in the classroom. Formula Student started my interest in robotics and self-driving cars and even made me change my degree. To put it simply, I owe much of what I am today to the Edinburgh University Formula Student (EUFS) team and all of the wonderful people behind it!

You can read more about this story at the University article about us or the team webpage